The Prescription—The Stacked Rappel

-

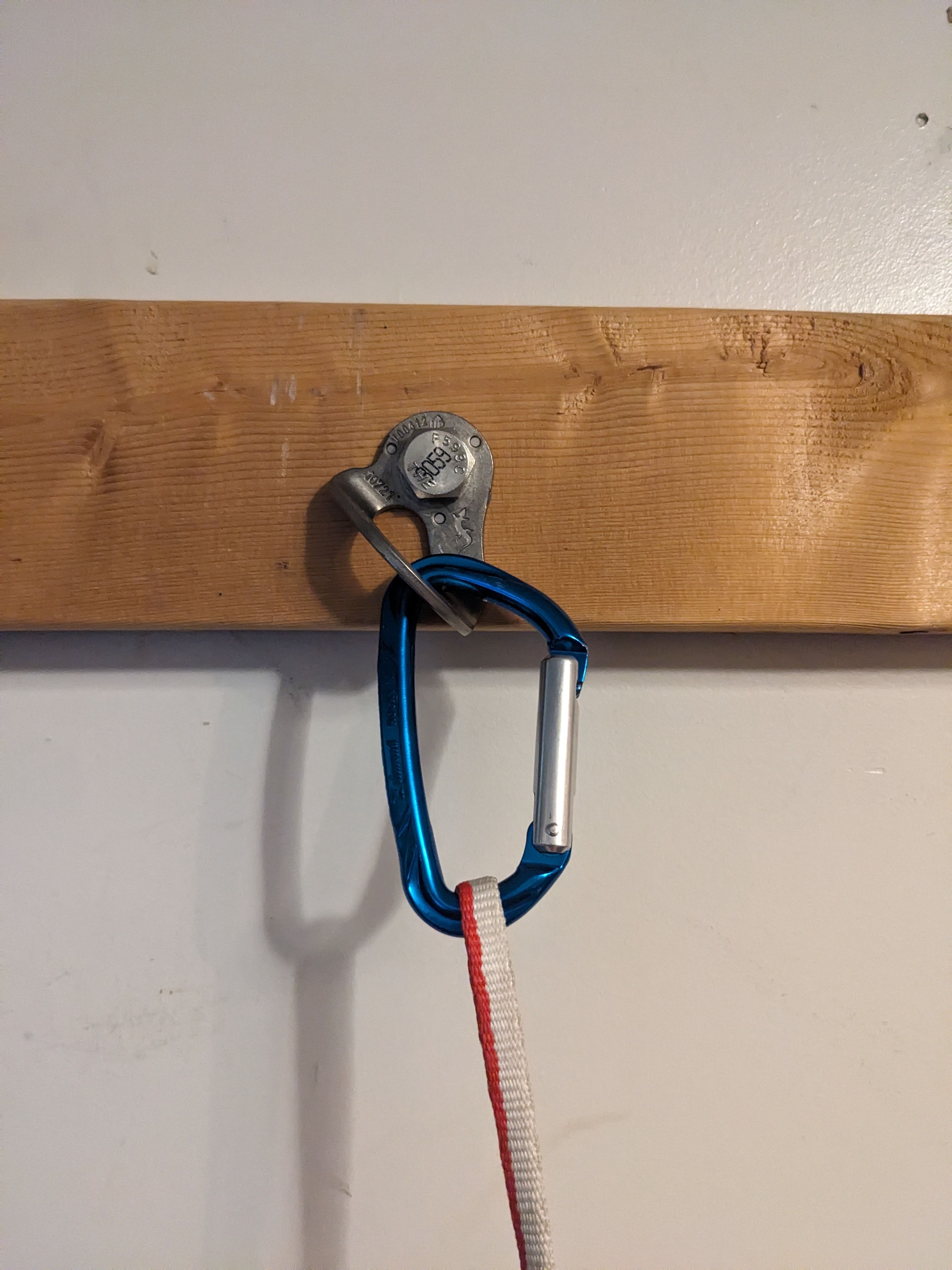

Rappelling is one of the most accident-prone facets of climbing, with improper/incomplete setup being an all-too-common cause of misadventure. In the 2025 ANAC, we featured an accident that involved a rappel fatality from a difficult ice/mixed route in the Canadian Rockies. Steep, multi-pitch winter climbing combines a challenging environment with the technical complexities of big-wall climbing. Gloved hands, copious gear, and often-cumbersome clothing can impede the usual streamlined rappel setup and safety checks. As John Godino mentioned in his 2025 ANAC Know the Ropes feature, the stacked rappel can help ameliorate these issues by promoting “More efficient rappels with reduced risk—what’s not to like?”

At the end of 2024, a very experienced climber named Dave Peabody (48) fell to his death while rappelling from a route on the Stanley Headwall. Alik Berg was Peabody’s partner on that day. Berg wrote to ANAC:

Dave and I had been regular climbing partners for about 12 years, with many seasons of winter, alpine, and rock climbing. On December 26, we headed to the Stanley Headwall to climb Drama Queen (170m, WI6 M7). This was a fairly routine climbing day for us. That morning, we saw teams on the neighboring climbs French Reality and Dawn of the Dead.

We topped out at dusk (around 5 p.m.) and began rappelling by headlamp. We both used an ATC-Guide on our belay loops and a prusik backup on our leg loops. The last pitch (P4) was the steepest, and we climbed on a single rope (blue) with the second rope (red) as a tag line. The pitch was short enough to be rappelled with the blue rope, while we left red fixed at the beginning of the pitch to pull ourselves back into the anchor atop P3.

This awkward rappel was partly free hanging, and pulling back into the belay required care to not disturb a large, dripping ice dagger. Dave descended first. I soon joined him. He had already begun setting up the next rappel, threading the red rope through the anchor and joining the two ropes with a single flat overhand knot.

The P3 anchor is a pair of modern bolts with Fixe rap rings. There was enough space on the small ice ledge to not be crowded, and we busied ourselves with the routine tasks of rigging the next rappel. I pulled the blue rope, verbally confirming with Dave that the joining knot was in place before making the final tug and pulling up the tail to add a stopper knot. We tied an additional stopper knot in the red rope before tossing it off. We noted a bit of a tangle in the red rope that we’d deal with on the way down.

Dave readied himself to start the rappel. I was distracted with untangling and tossing the remaining rope from the ledge and did not directly observe his connection to the ropes. He started the rappel, moving normally. As Dave descended, my gaze at that moment was on the overhand knot joining the rope ends. I sensed something was off but couldn’t register what it was.

At this point, Dave fell. The interval between sensing something was amiss to when Dave started falling was very short, maybe one to two seconds or fewer. There was enough time to register this thought but not enough to assess, let alone react. I believe he was about five to 10 meters below the anchor when he fell—not when he first stepped off the ledge and weighted the system.

In the immediate aftermath, I became fixated on something being “off” with the knot and that being the likely point of failure. It wasn’t until reaching the ground the next morning that it became clear that the knot was not the cause of the accident.

When Dave fell, I reacted by grabbing the free-running (red) rope and squeezing hard enough to melt my gloves and burn my fingers, but not enough to slow his fall. In the darkness, I could not see him at the base, only the faint glow of his headlamp. It was about 6 p.m.

The team on French Reality had already left the area. The party on Dawn of the Dead had descended, traversed the base of the wall, and were around the corner and out of earshot. About 15 minutes after the accident, their headlamps reappeared as they looped back into view near valley bottom—about one kilometer northwest of my location. I was able to yell down, and they turned around. At 6:45 p.m., they reached the base, and we could communicate properly. It was then that they realized the severity of the situation and activated their inReach.

Dave and I had both carried a cell ...

The Prescription—The Stacked Rappel — American Alpine Club

Rappelling is one of the most accident-prone facets of climbing, with improper/incomplete setup being an all-too-common cause of misadventure. In the 2025 ANAC , we featured an accident that involved a rappel fatality from a difficult ice/mixed route in the Canadian Rockies. Steep, multi-pitch wi

American Alpine Club (americanalpineclub.org)